June 23, 2017

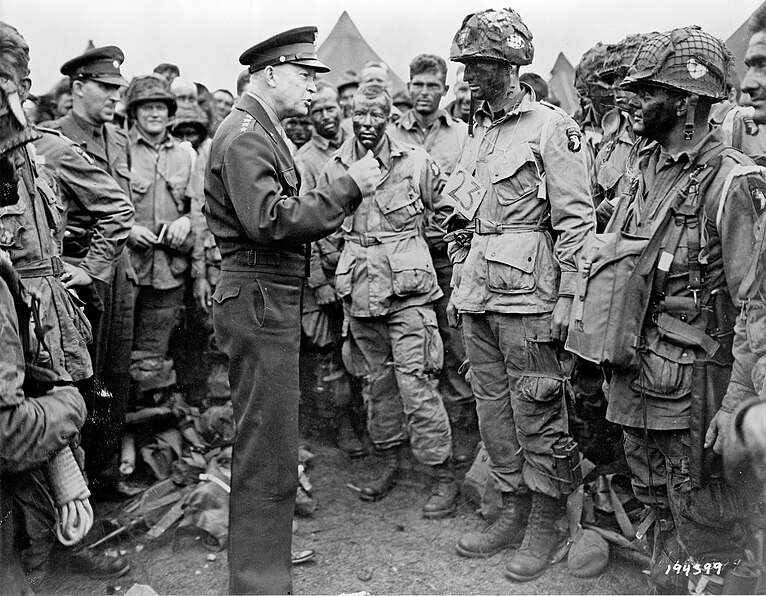

Tennessee coach Pat Summitt in huddle with team during timeout of game vs Louisiana State, Baton Rouge, LA 2/10/2005 (Getty Images)

This week marks a dual commemoration: the 45th anniversary of the signing of Title IX coincides with the first anniversary of the passing of Pat Summitt, who turned that law into such an equal rights spear for women. So it seems right to dwell for a moment on the collective state of young women athletes on campuses today, to ask whether they are weaker or stronger than yesterday — and whether Pat could be the same kind of force for them in this current snowflakey, iGen safe- space climate. The truth? She might get herself fired.

The data shows that since Summitt left coaching in 2011, women athletes have become more anxious, more prone to depression, less adult, and more insecure than ever before. What is up with that?

According to a 2016 NCAA survey, 76 percent of all Division I women athletes said they would like to go home to their moms and dads more often, and 64 percent said they communicate with their parents at least once a day, a number that rises to 73 percent among women’s basketball players. And nearly a third reported feeling overwhelmed.

Social psychologists say these numbers aren’t surprising, but rather reflect a larger trend in all college students that is attributable at least in part to a culture of hovering parental-involvement, participation trophies, and constant connectivity via smartphones and social media, which has not made adolescents more secure and independent, but less.

Since 2012, there has been a pronounced spike in mental health issues on campuses, with almost 58 percent of students reporting anxiety, and 35 percent experiencing depression, according to annual freshman surveys and other assessments.

Research psychologist Jean Twenge wrote a forthcoming book pointedly entitled “IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.” She says that the new generation of students is preoccupied with safety. “Including what they call ‘emotional safety,’ ” she said. “Perhaps because they grew up interacting online and through text, they believe words can incur damage.”

At the same time, accompanying this anxiety, iGens have unrealistic expectations and exaggerated opinions of themselves. Nearly 60 percent of high school students say they expect to get a graduate degree — when just 9 to 10 percent actually will. And 47 percent of Division I women’s basketball players think it’s at least “somewhat likely” they will play professional or Olympic ball, but the reality? The WNBA drafts just 36 players, 0.9 percent.

“If you compare iGen to Gen-Xers or boomers, they are much more likely to say their abilities are ‘above average,’ ” Twenge said.

This combination of dissonant factors is creating an increasingly tense relationship between overconfident yet anxious players, and coaches who bring them down to earth. In women’s sports especially, there has been an ugly surge in complaints of “verbal abuse,” with investigations at more than a dozen programs between 2010-2016. In some cases, coaches were relieved for legitimate cause. But in others, good decorated coaches were suspended, fired, or resigned even though there was no evidence of mistreatment. At Nebraska, Connie Yori, was the 2010 coach of the year and took the Cornhuskers to a Big 12 regular season title, a Big Ten tournament title and seven NCAA tournaments in 14 years, before she quit last season in the wake of complaints that she was “overly critical” of players, and made them weigh themselves.

Something more is going on here than a new awareness of bullying, and rebellion against fossilized methods.

Talk to coaches, and they will tell you they believe their players are harder to teach, and to reach, and that disciplining is beginning to feel professionally dangerous. Not even U-Conn.’s virtuoso coach Geno Auriemma is immune to this feeling, about which he delivered a soliloquy at the Final Four.

“Recruiting enthusiastic kids is harder than it’s ever been,” he said. “. . . They haven’t even figured out which foot to use as a pivot foot and they’re gonna act like they’re really good players. You see it all the time.”

Coaches are so concerned about this that at the annual Women’s Basketball Coaches Association spring meeting they brought in no fewer than three speakers to address it. Youth-motivator Tim Elmore lectured on “Understanding Generation iY.” And a pair of doctors discussed “Promoting Mental Health Strategies and Awareness.”

It doesn’t take a social psychologist to perceive that at least some of today’s coach-player strain results from the misunderstanding of what the job of a coach is, and how it’s different from that of a parent. This is a distinction that admittedly can get murky. The coach-player relationship has odd complexities and semi-intimacies, yet a critical distance too. It’s not like any other bond or power structure. A parent may seek to smooth a path, but the coach has to point out the hard road to be traversed, and it’s not their job to find the shortcuts. Coaches can’t afford to feel sorry for players; they are there to stop them from feeling sorry for themselves.

oaches are not substitute parents; they’re the people parents send their children to for a strange alchemical balance of toughening yet safekeeping, dream facilitating yet discipline and reality check. The vast majority of what a coach teaches is not how to succeed, but how to shoulder unwanted responsibility and deal with unfairness and diminished role playing, because without those acceptances success is impossible.

Players can let that demoralize them — or shape them into someone stronger. The choice is ultimately theirs, not the coach’s. And that’s the thing most people miss about coaches: how strangely powerful yet powerless they ultimately are, how beholden they are to the aspirations and frailties of other people’s children. It’s a beautiful, terrible relationship that can tilt all too easily, and usually tilts hard, into undying loyalty or lifelong hard feelings.

The bottom line is that coaches have a truly delicate job ahead of them with iGens. They must find a way to establish themselves as firm allies of players who are more easily wounded than ever before yet demand they earn praise through genuine accomplishment.

Based on what I knew of Pat and her intuitive dealings with vulnerable players such as Chamique Holdsclaw, who has become a powerful campus mental health advocate, she probably would have found a way to work with and build up iGens, just as she did boomers, Gen Xers, and millennials. But it would not have been an easy adaptation.

Believe it or not, for most of Summitt’s 1,098-victory career at Tennessee, what she really taught was how to deal with fear and falling. In the 21 years I knew her, only three times did she win championships. All the rest of those seasons ended in some kind of failure.

Much as she loved to see her players win, what she was really interested in was “how they respond,” she said. She said time and again that what she really was trying to do was convert girls into strong, independent women. It was an inevitably painful undertaking.

“If everyone loved it all the time,” she said, “that meant we were doing something wrong.”